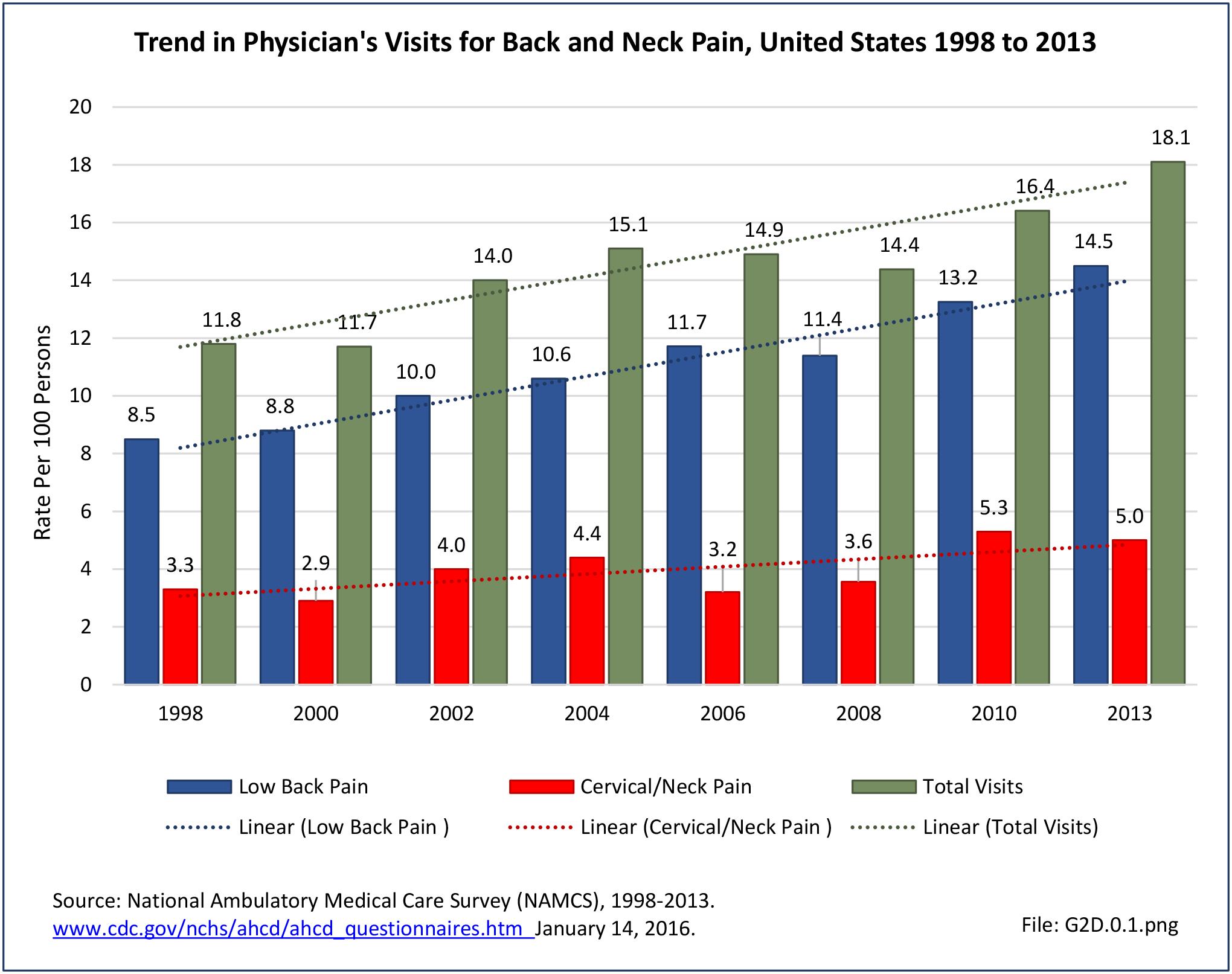

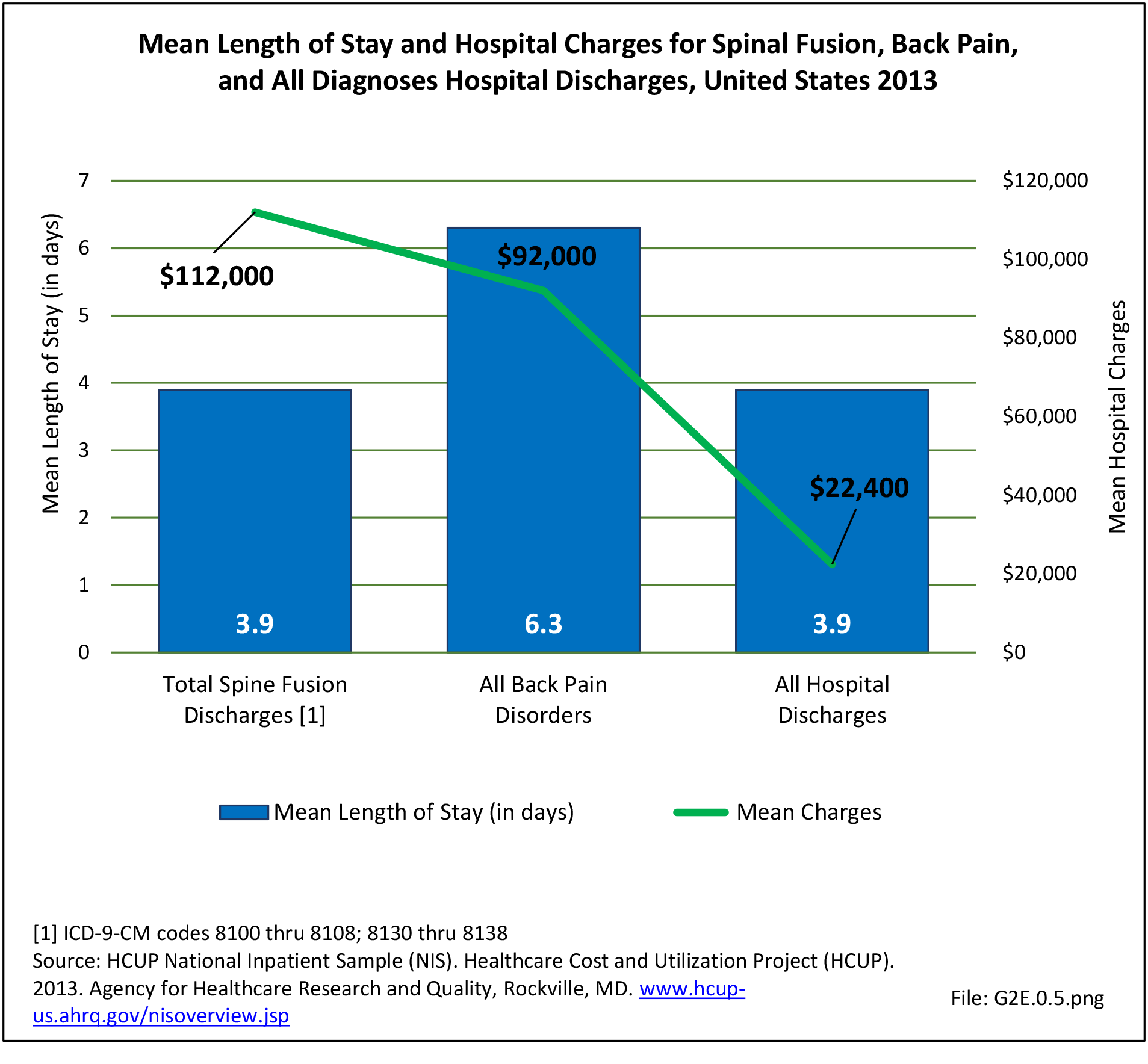

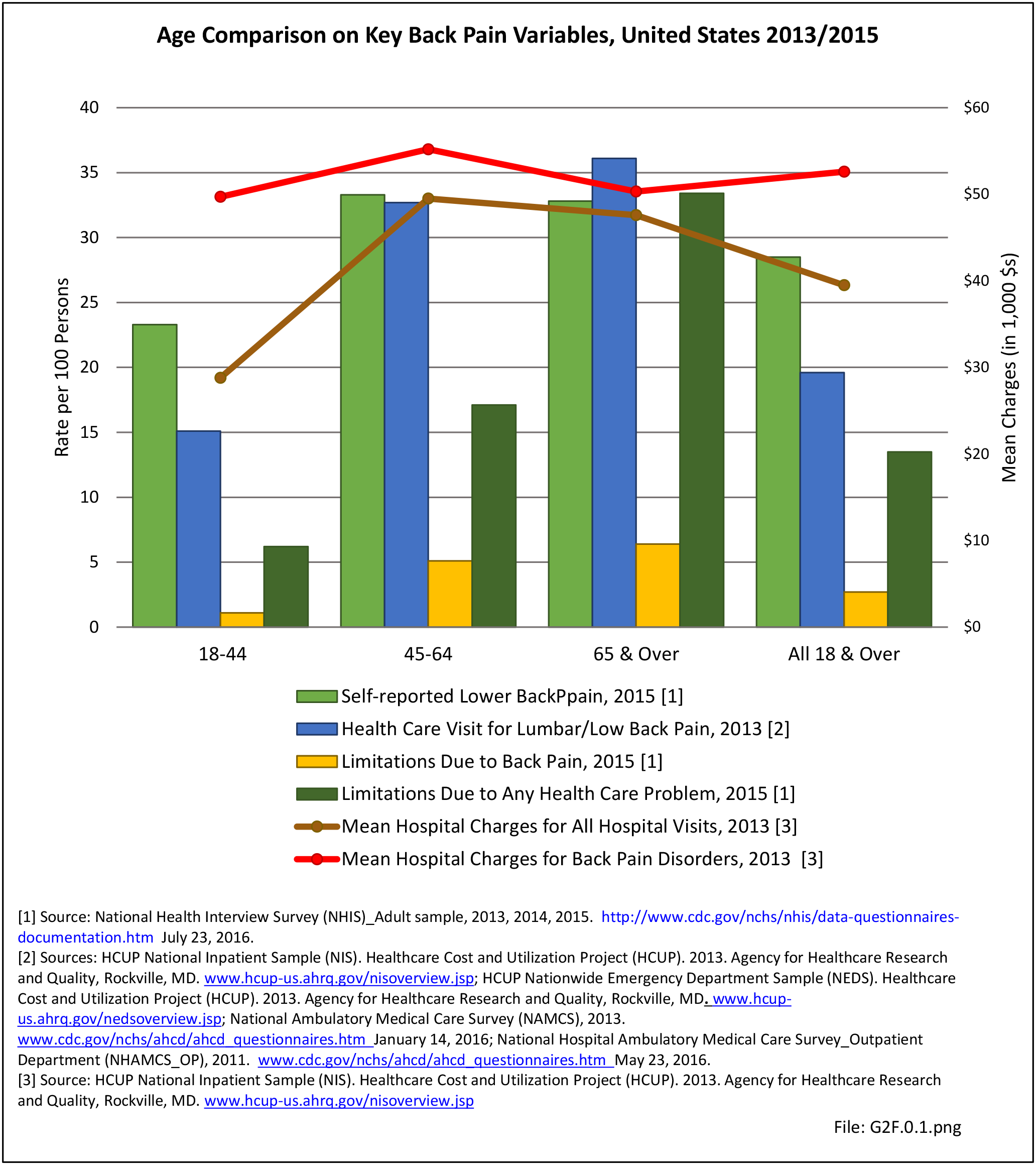

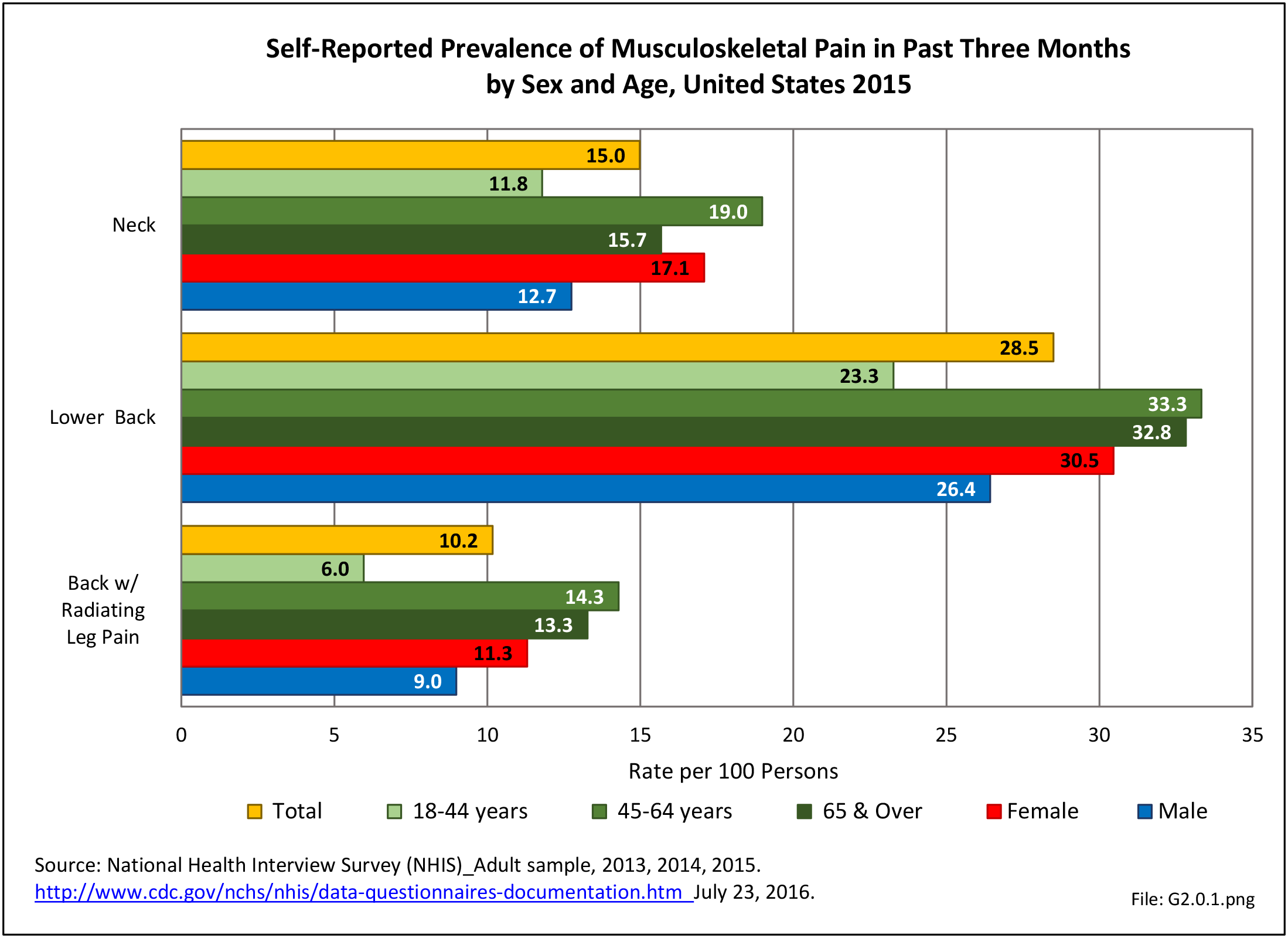

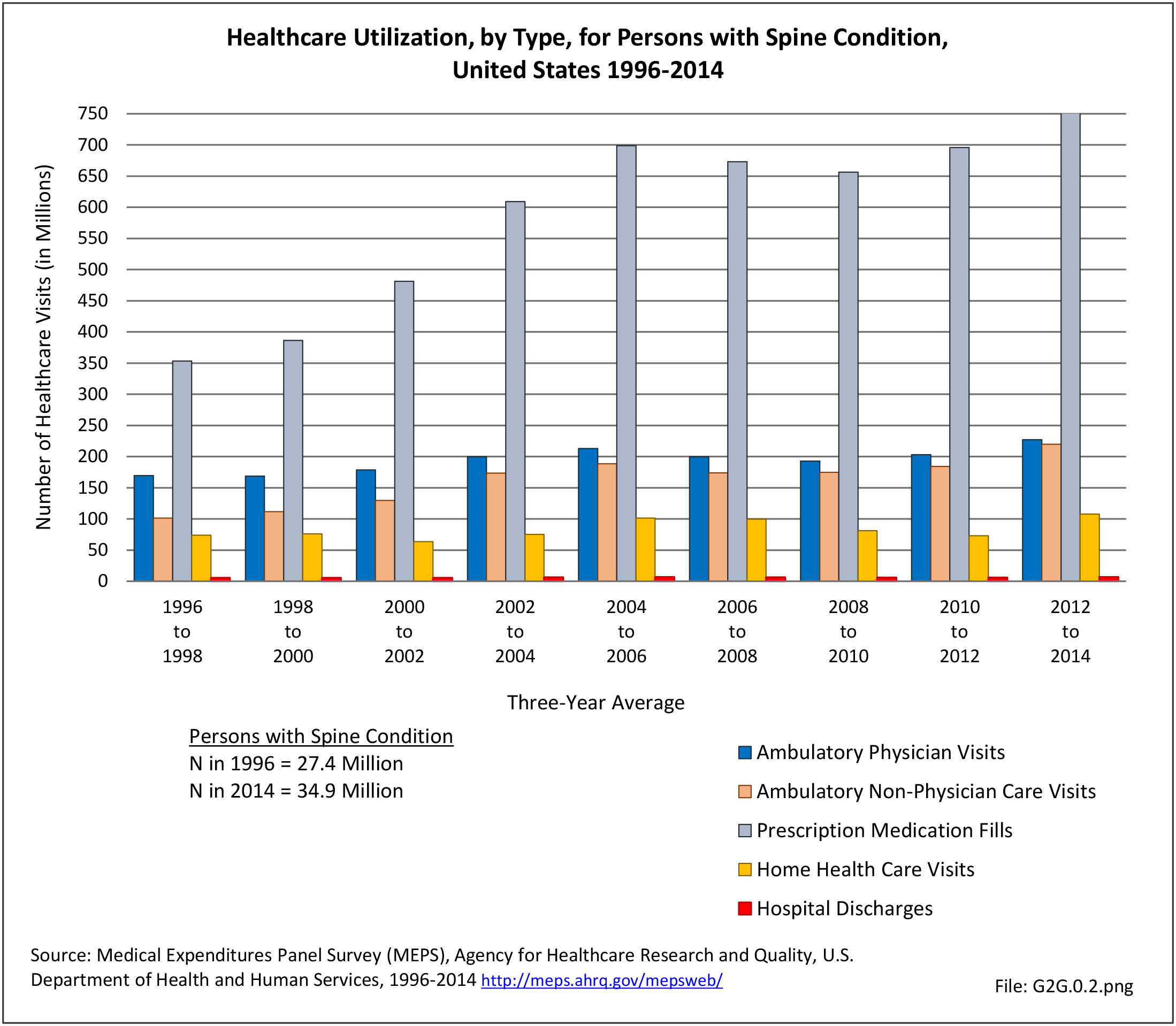

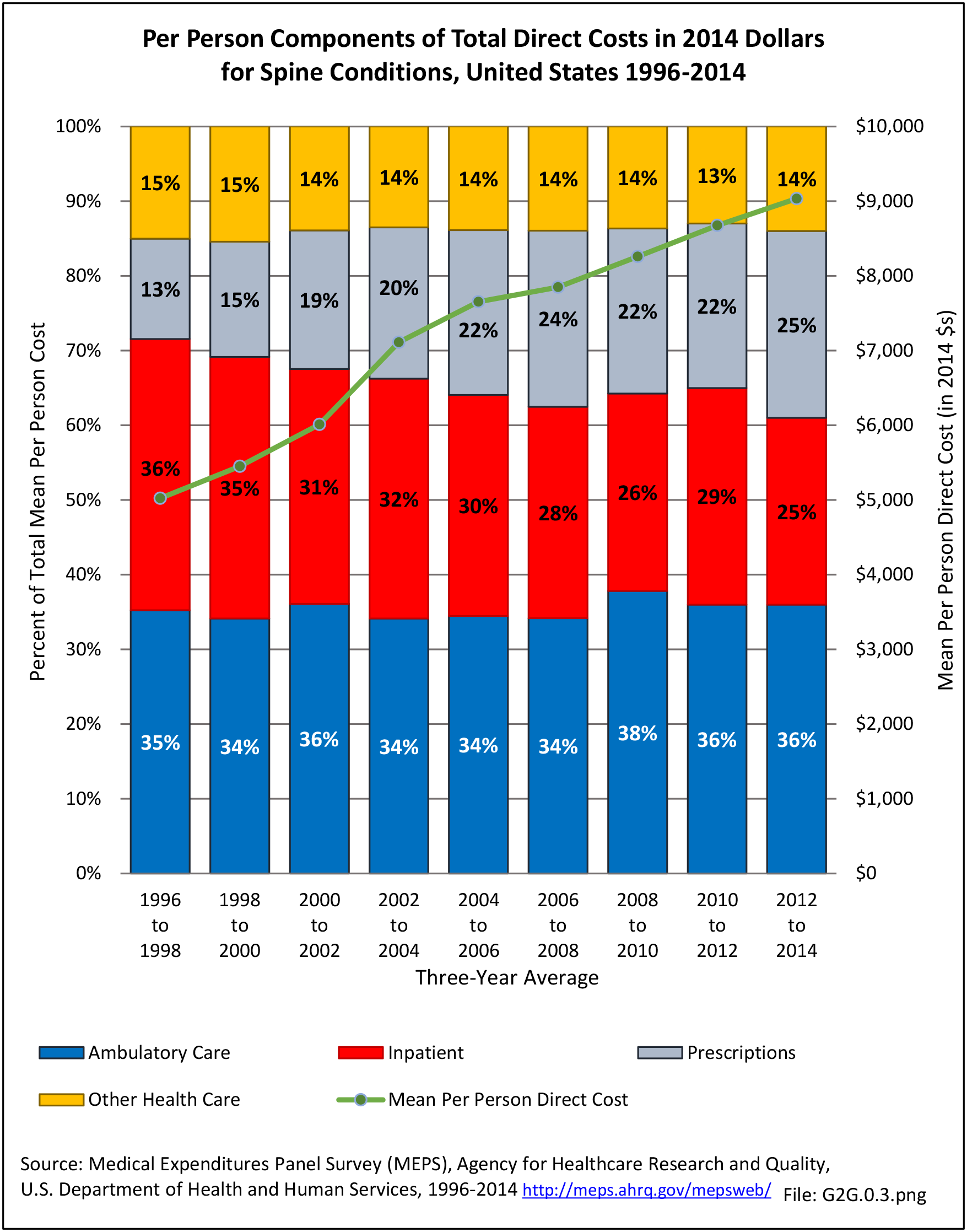

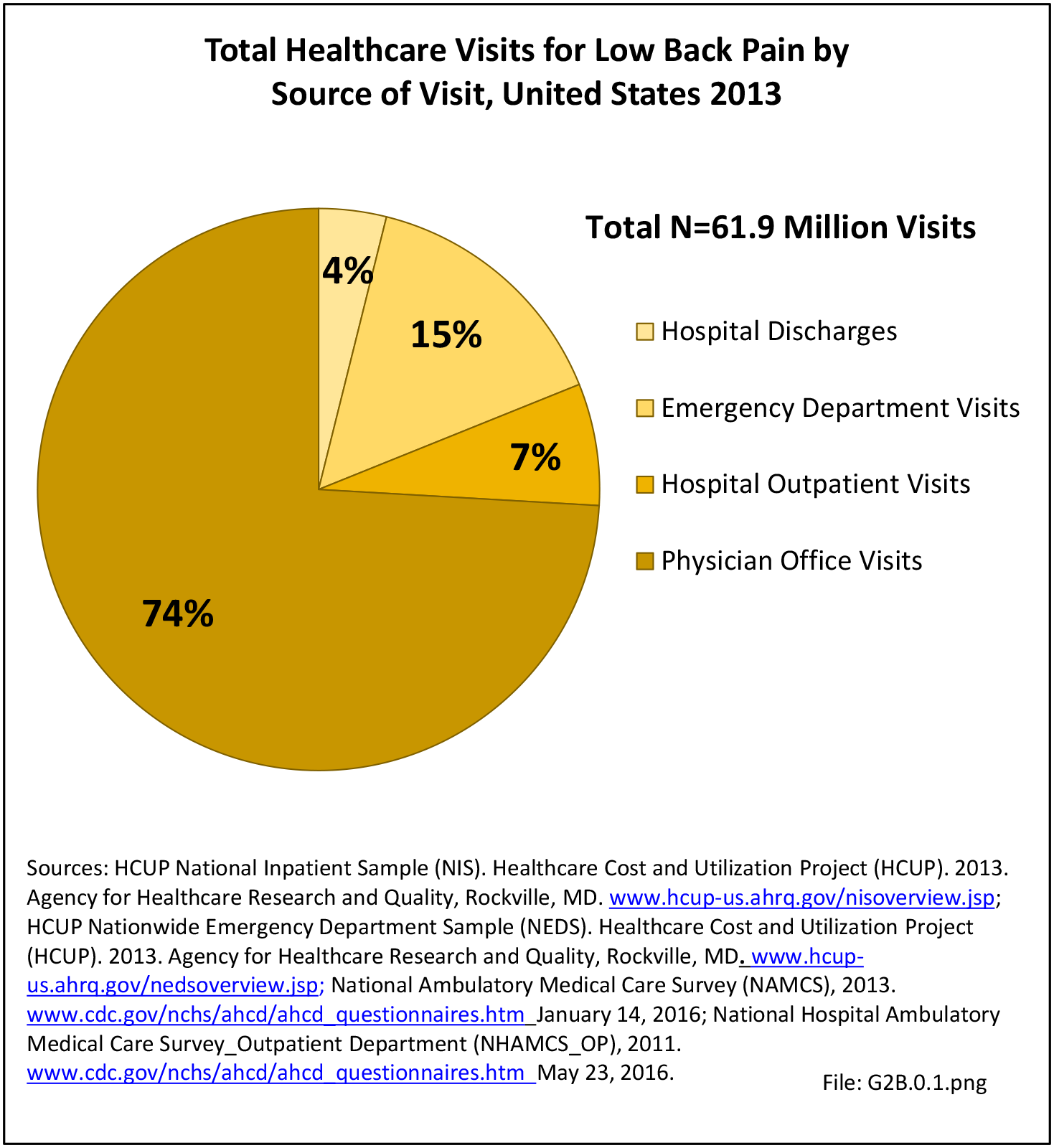

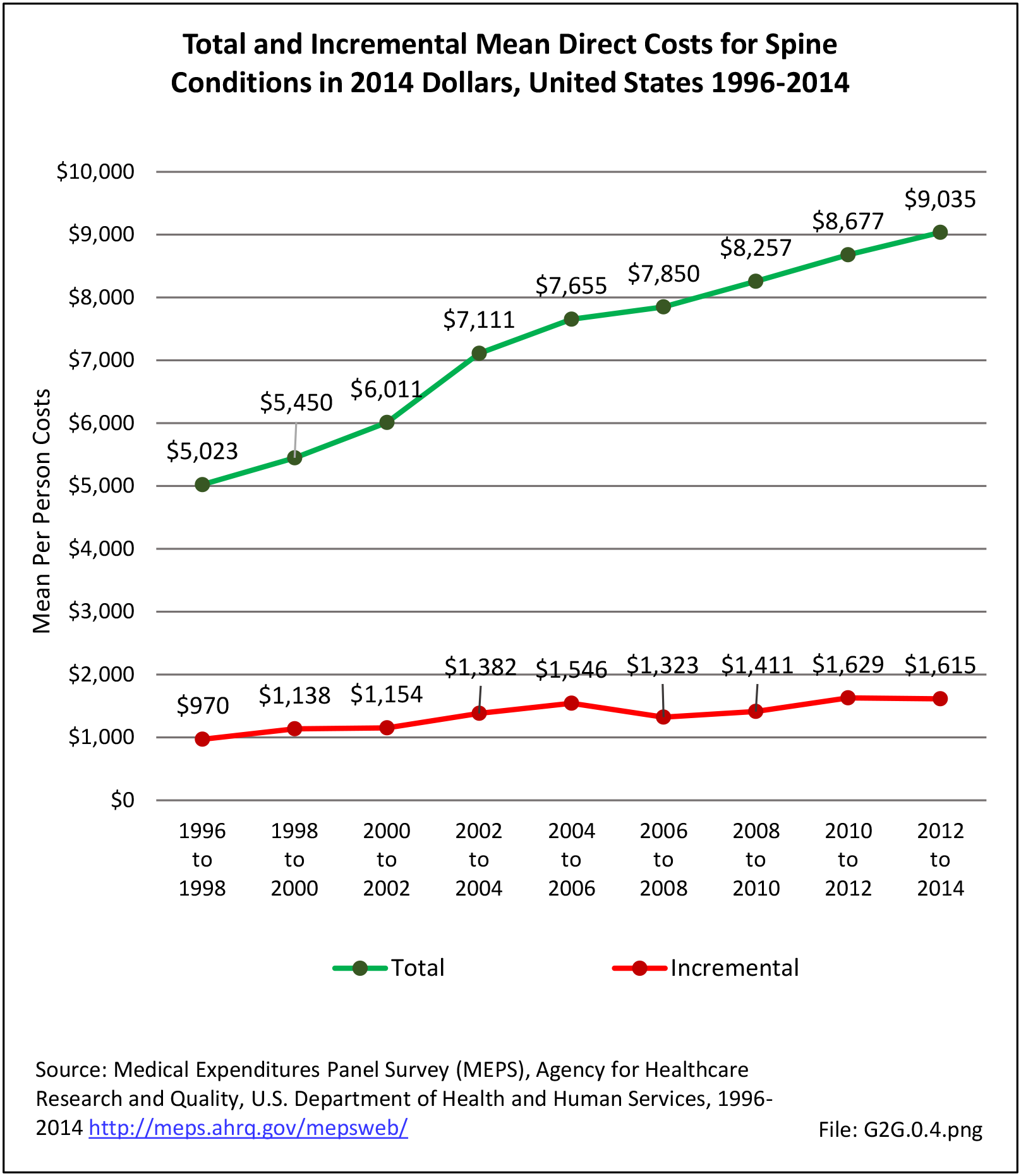

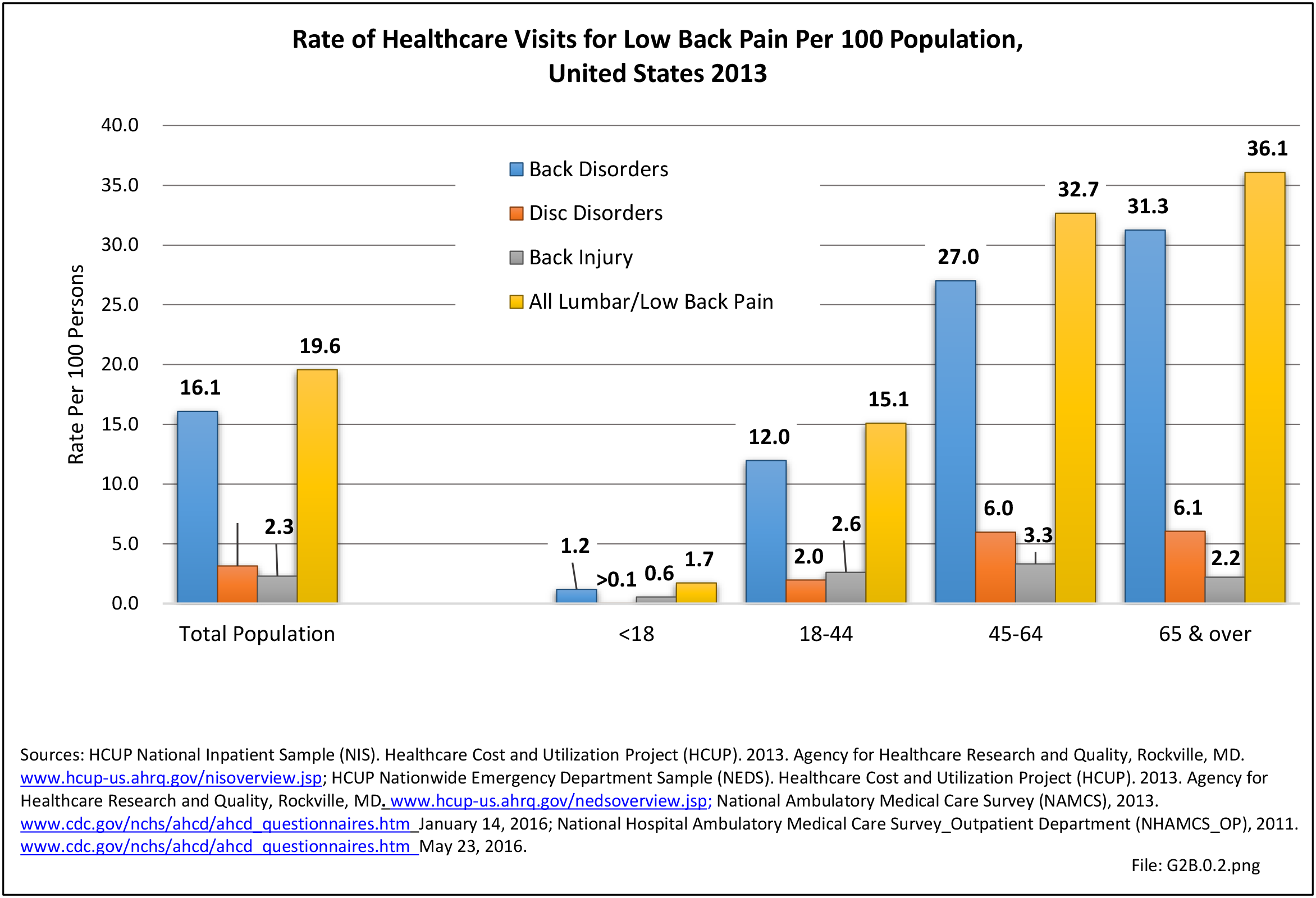

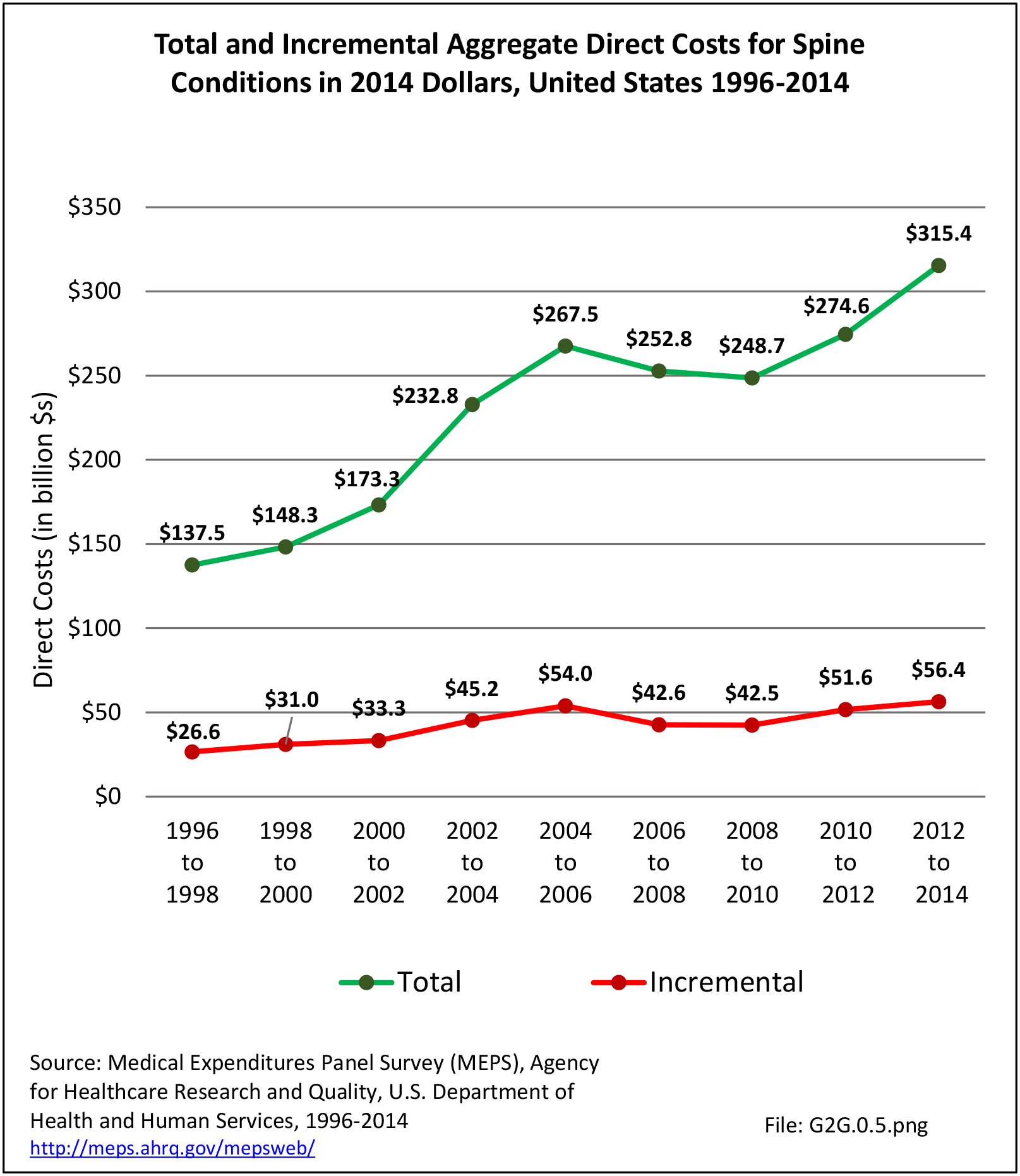

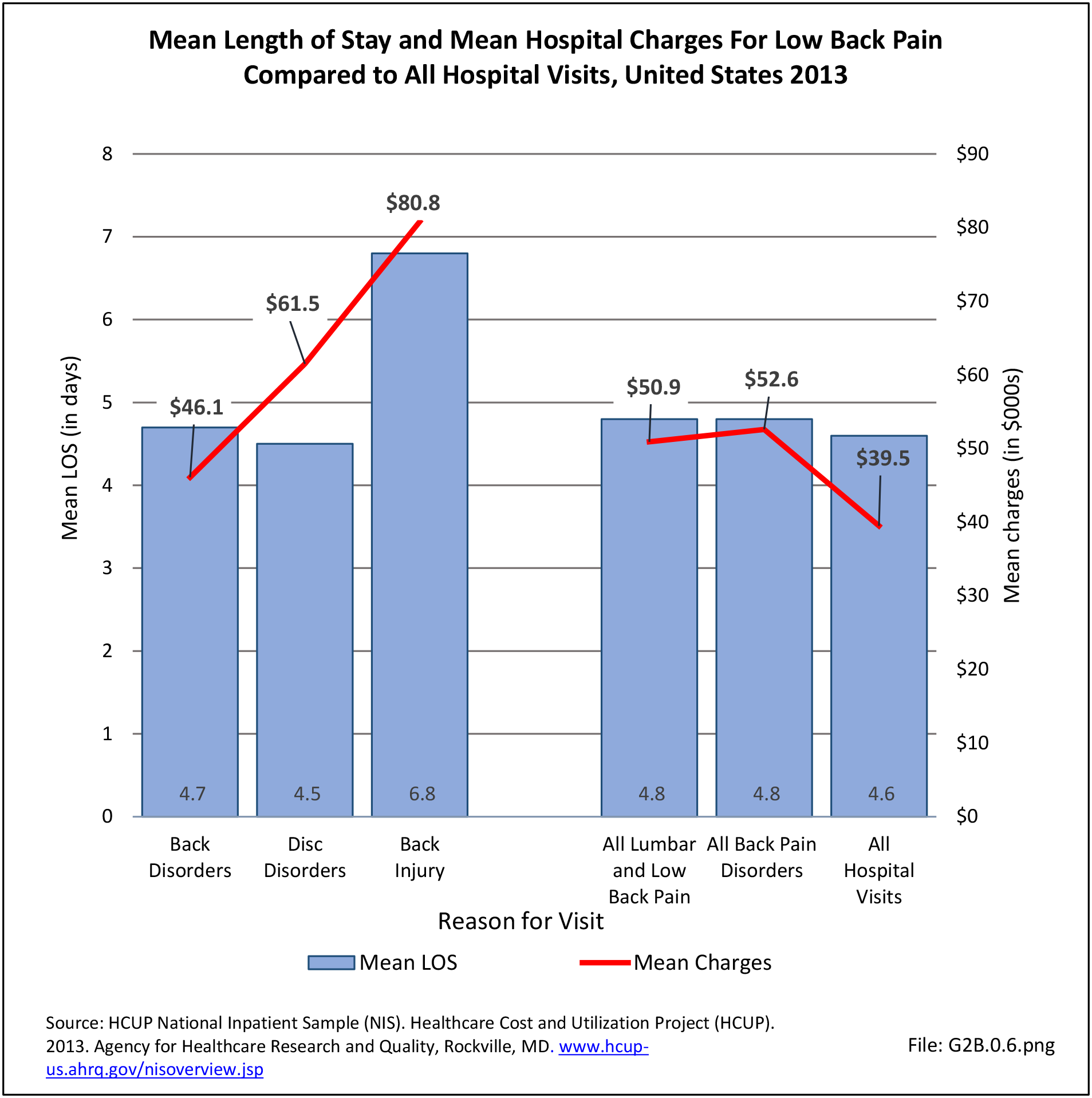

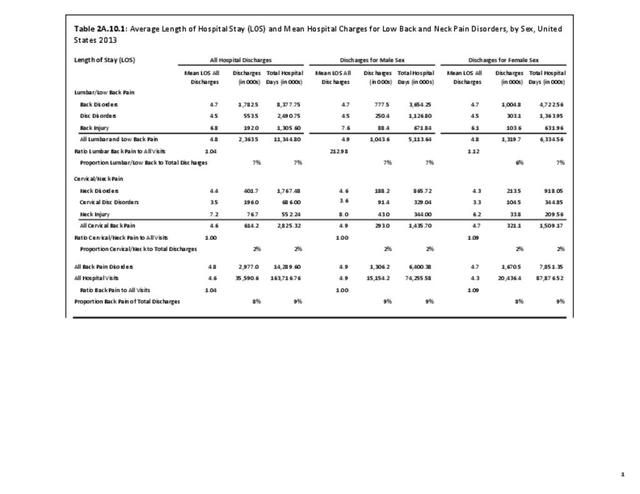

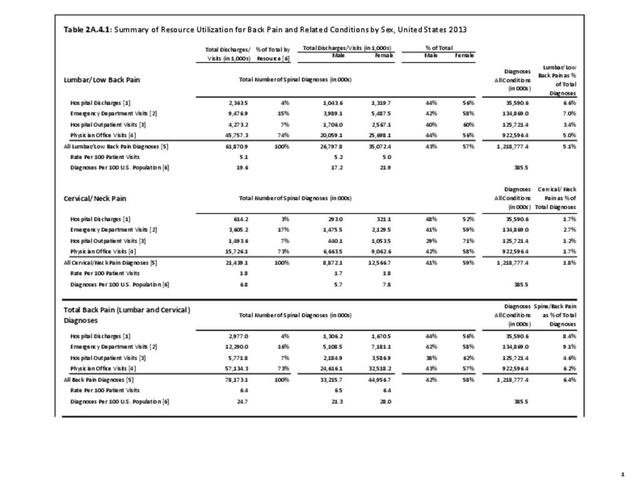

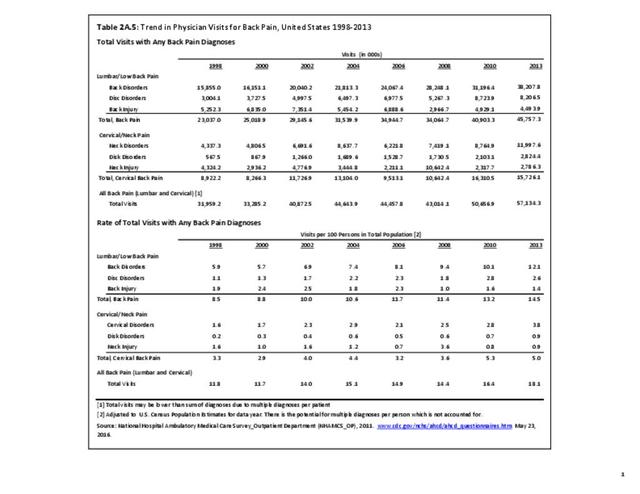

The financial cost associated with back pain is obviously enormous and, unfortunately, rising. At the current rate of increase, back pain treatment will quickly become unsustainable. Greater understanding of the underlying causes of back pain, ability to sub-classify patients based on accurate pain generators (eg, discogenic pain, facet mediated pain, radicular pain) and what factors lead to disability (ie, biological, psychological, or social) is needed to reduce this continually increasing trend. Ideally, understanding the variability of individual sources of and contributions to back pain could direct clinicians to specific treatments that best address the diagnosis.

The cost and difficulty of back pain research is also a major challenge. The complexity of back pain diagnosis and treatment options make high quality clinical research with meaningful results very difficult to fund and complete. This requires large scale multi-center trials with well-educated research staff and patients willing to stick with randomized modes of treatment. The latter consideration is often very difficult to obtain in a system where patients want immediate results. In addition, many non-surgical, non-pharmacological providers use a multimodal approach to care rather than an isolated intervention, complicating efforts to identify which treatment is most effective.

Adding to this challenge may be the subjective nature of pain. It is often very difficult, if not impossible, to separate psychological or emotional pain that is greatly influenced by the social environment from physiologic pain caused by a specific physical source. Differentiating between the two categories will play a tremendous role in our ability to treat patients in pain. Societal perceptions about back pain have been shown to lead to catastrophization, a common cognitive distortion extensively studied in psychology that is an irrational thought or belief that something is far worse than it actually is. Studies in pain patients have found catastrophization to be a significant factor in their disability and response to treatment.

System integration of historically fringe practitioners is a challenge as we attempt to grow effective non-surgical management strategies such as acupuncture, massage, tai chi, yoga, and chiropractic. Training practitioners to provide evidence-based informed care plans and appropriate referrals for other services or emergent conditions should start early in medical training. Improved graduate and post-graduate education which includes integrating educational tracks to better understand different disciplines of care and what they can offer can create a shared common base of critical thinking. For example, Denmark provides the first year medical school education to chiropractors and physicians jointly before diverging to more specific training.

Another challenge to the future is our healthcare financial system. Treatment decisions are too often made based on financial limitation rather than best clinical practice. Clinical decisions may be limited by insurance authorizations or treatment decisions, and could be influenced by highest reimbursement. Cost-effectiveness and risk/benefit discussions for alternative options are essential to providing successful treatments and reducing costs.

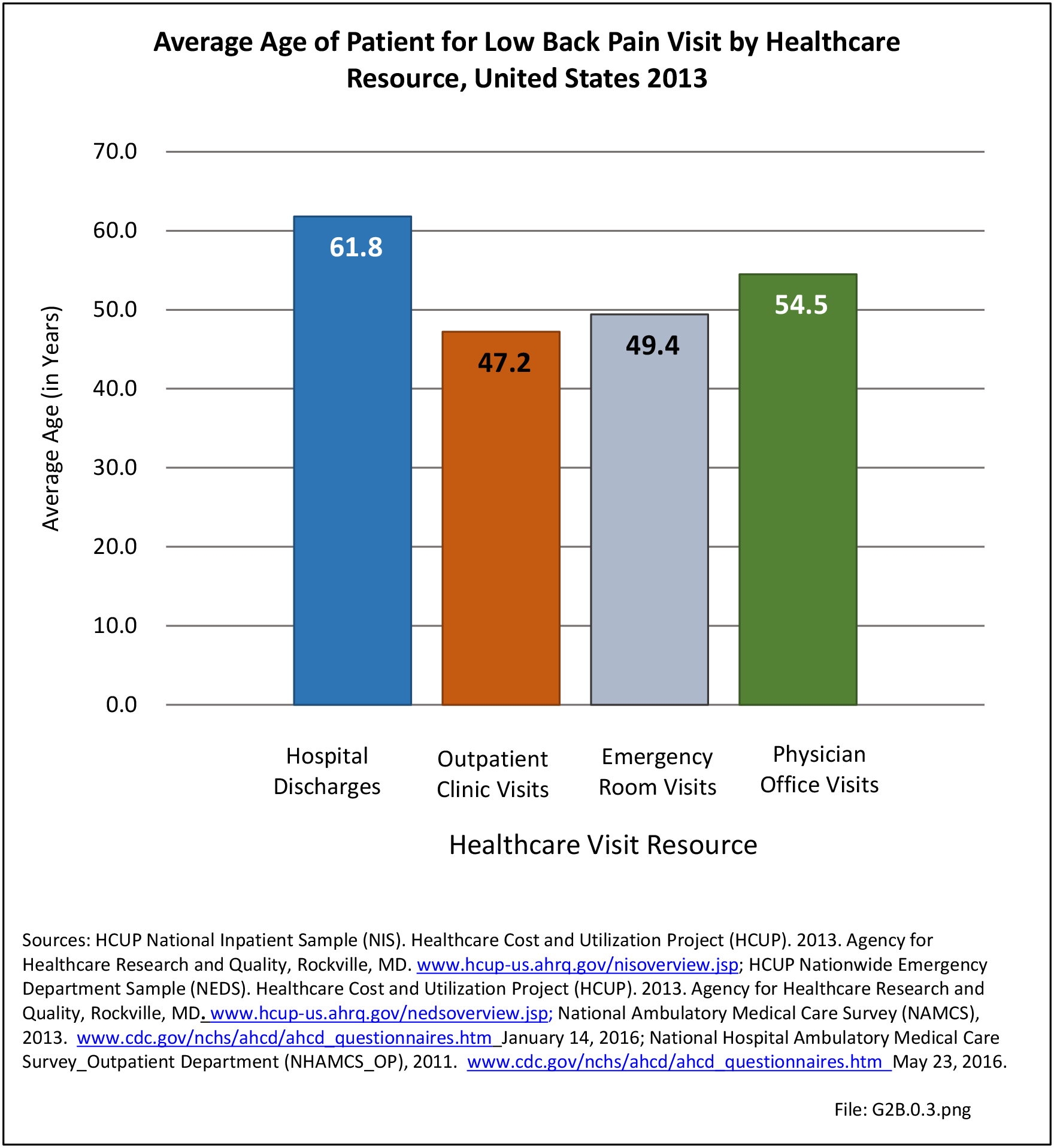

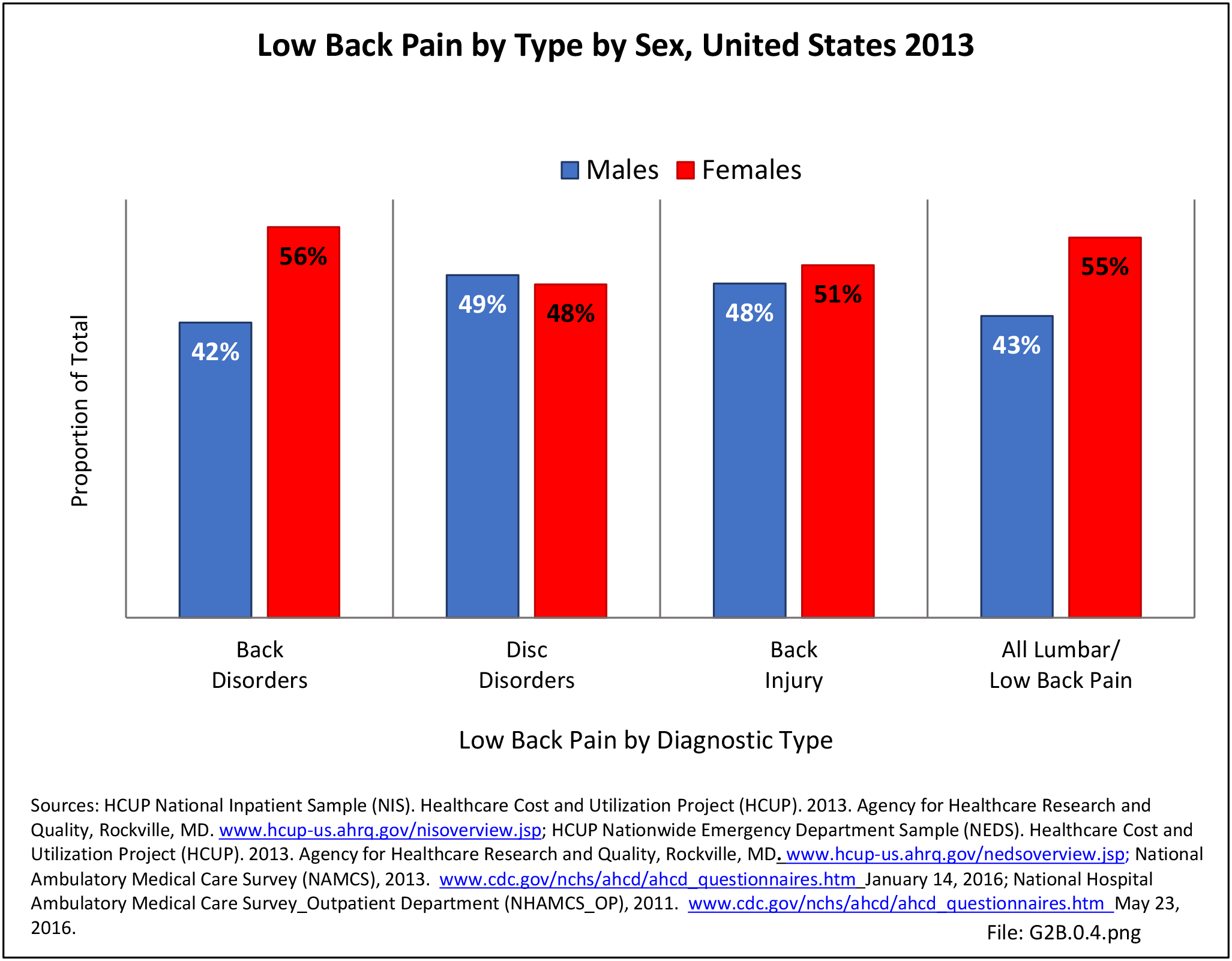

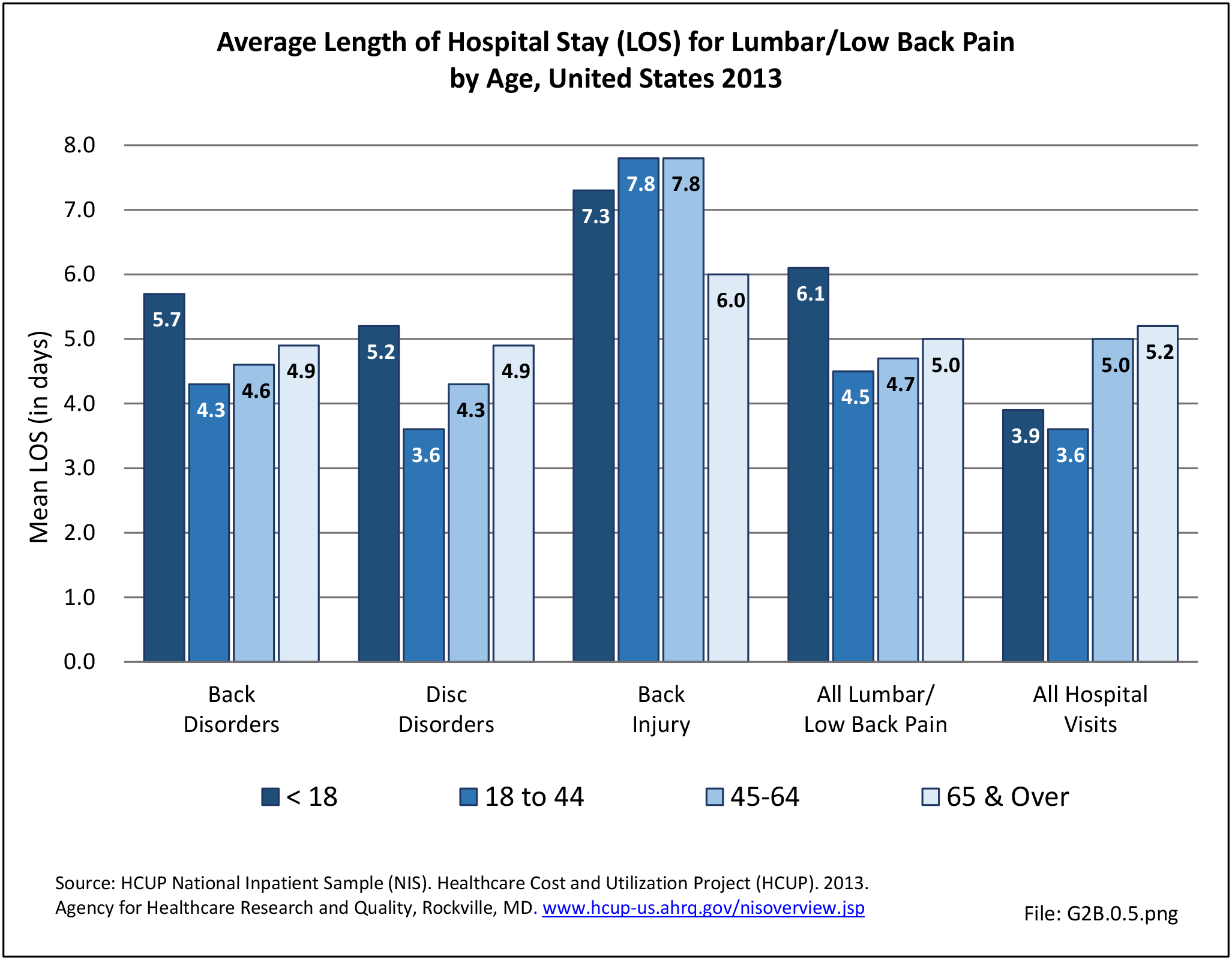

Understanding why the degenerative cascade causes pain in some, yet not in others, is needed to address the burden of pain and disability and the significant economic impact low back pain treatments create on healthcare resources each year.

Edition:

- Fourth Edition