The burden of musculoskeletal issues on the military population cannot be overstated. Further, the impact of these injuries does not stop when the service member transitions out of the military. Musculoskeletal injuries and conditions are one of the greatest threats to our military’s readiness and troops ability to deploy and as such, bear a substantial significance for our society as a whole.1,2 Further, inability to return to full duty due to musculoskeletal injury or pre-existing musculoskeletal condition is the most common reason for medical discharge from the Armed Services across all branches,3,4 with almost 78% of male Army personnel and 85% of females with a disability discharge discharged due to a musculoskeletal injury or condition.4 There is anecdotal and some scientific evidence on medical discharges from the British armed forces that females in military service experience an excess of work-related injuries, compared with males.5

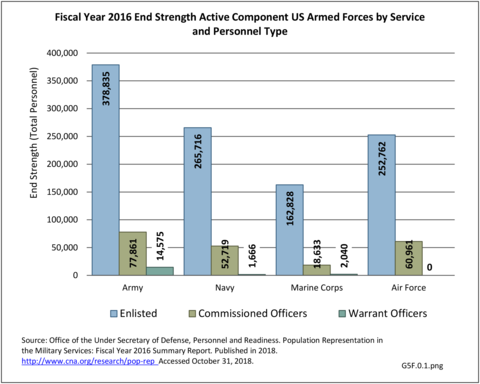

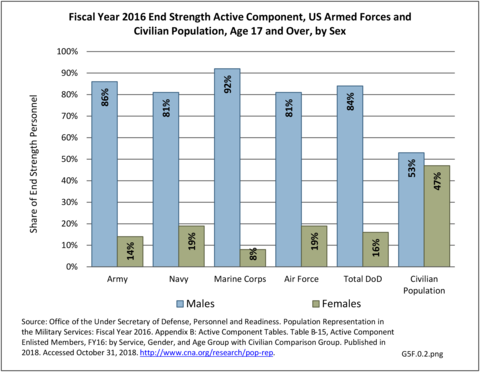

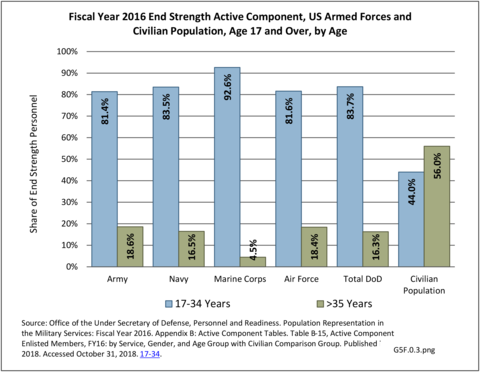

During Fiscal Year 2016, there were nearly 1.3 million active duty service members (enlisted plus officers) and an additional 860,000 Reserve and National Guard members. Among all branches of the Department of Defense enlisted personnel (1.06 million), 84% are male and 16% female. Female personnel were slightly younger, with 86% under the age of 35, compared to 83% of male personnel under 35 years of age. This is nearly double the percentage of the civilian population under age 35, years where in both male and female persons only 44% is under 35 years of age. The Marine Corps has the highest proportion of personnel under the age of 35 years, with 92.5% of the enlisted component of the Marine Corps less than 35 years. The young age and high activity level of the active duty military population brings about a unique set of musculoskeletal conditions. (Reference Table 5F.0.1 PDF CSV and Table 5F.0.2 PDF CSV) (G5F.0.1, G5F.0.2, G5F.0.3)

- 1. Jones BH, Canham-Chervak M, Sleet DA. An evidence-based public health approach to injury priorities and prevention recommendations for the U.S. military. Am J Prev Med 2010; 38(1 Suppl):S1-10. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.001.

- 2. Cameron KL, Owens BD. The burden and management of sports-related musculoskeletal injuries and conditions within the US military. Clin Sports Med 2014; 33(4): 573-589.

- 3. Ministry of Defence. Annual medical discharges in the UK regular armed forces: 1 April 2013 to 31 March 2018. July 12, 2018. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/medical-discharges-among-uk-se... . Accessed November 29, 2018.

- 4. a. b. Piccirillo AL, Packnett ER, Cowan DN, Boivin MR. Risk factors for disability discharge in enlisted Active Duty Army soldiers. Disabil Heath J. 2016 Apr;9(2):324-331.

- 5. Geary KG, Irvine D, Croft AM. Does military service damage females? An analysis of medical discharge data in the British armed forces. Occupational Medicine. April 2002. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/11401381_Does_military_service_.... Accessed February 2, 2019.

Edition:

- Fourth Edition